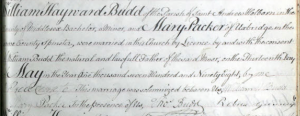

William Hayward Budd is an enigma. No doubt about it. Patriarch of a large family that was seemingly born into relatively humble circumstances, his children went on to great things. William, having married a vicar’s daughter, Ann Hayward in 1774, was an Inn Keeper (of some repute and standing), but it appears that the significant capital outlay required to refurbish the Crown Inn at Uxbridge in the early 1790s was too much for him and he was declared bankrupt in 1794. Despite this setback, William was a social networker of his time and used any and all connections he had to secure patronage and advancement for his children.

Of the twelve children that can be traced, a brief summary of their lives is as follows:

Ann (eldest daughter) Married Benedict John Angell, joining a wealthy family of landowners

Elizabeth Hayward Married Charles Barrington who went on to establish a place named after him in Nova Scotia, Canada

Thomas Hayward Married Marie Ann Reinagle, daughter of a Royal Academician and became a wealthy solicitor in London

Hopewell Hayward Joined Royal Navy and became a protege of Sir Sidney Smith (a peer of Nelson), retired a Commander

Henry Hayward Ditto

George Hayward Joined the Madras Native Infantry, sponsored by George Thelusson, a Director of The East India Company

Edward Hayward Sponsored into the War Office by William Wyndham, Secretary of War, went on to become one of the best known cricketers of his generation

Charles Hayward Became a Land Agent in London

Richard Hayward Became a Vet and emigrated to America

Samuel Hayward Gained a commission in Dillon’s Regiment

William Hayward Perhaps most like his father, Postman, then Waggoner, also declared bankrupt

These children were no slouches! Due to their status, much can be found in public records about their lives (and their tombs are invariably impressive, bearing testament to their standing). It’s clear that William worked Georgian patronage relentlessly.

But what’s also interesting is that his patronage seems much diminished from 1800 (George entered the Madras Native Infantry not through his father’s connections, but his bother’s, Thomas) – one cannot help making the connection with his Bankruptcy, declared in late 1799.

William’s later life can be pieced together as follows:

1799. August – Declared bankrupt. Sale of the Crown and Cushion, the Inn he leased from the Evans family – comprising ‘thirty two good sleeping rooms, seven dining rooms, an elegant spacious assembly room…stabling for one hundred horses…meadow land nearby adjoining…fifty two acres of meadowland…household furniture, plate, linen, china, horses…’

1800. Still a tenant of Mrs Evans. We know that from the Uxbridge Tax records that Crown and Cushion is demolished by 1804.

Here’s where the story can only, at this stage, be a hypothesis.

1801. William Budd is recorded in the Salisbury and Wiltshire Journal as being a licensed Gamekeeper to BJ Angell (Husband of William’s eldest daughter Ann), in Studley, Calne. These records persist, on and off, until 1812 (at this stage, William would be 65 years old, if you believe how this hypothesis ends).

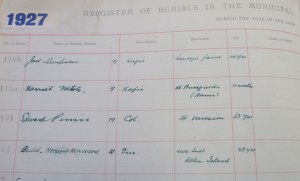

The next mention of William Budd in Studley is also in the Salisbury and Wilts Journal, citing the death of a William Budd, of Rumsey Cottage, Calne, on 20 Jan 1821 ‘aged 75 years after a long illness which he bore with christian fortitude.’

I think that the chances of this not being our William are very slim – this appears to be a cottage on the Angell estate and my belief is that Ann installed her aged father there for the final years of his life. I expect he lived there from 1801 but cannot prove that at this stage. Being a recent bankrupt, my theory is that she supported him by installing him on the estate in 1801 (and the last definitive record of him in Uxbridge is as a tenant of Mrs Davies in 1800).

We should remember that he still had four dependent children at that time – George (14), Charles (12), Richard (10), and Samuel (9). When Samuel applied to re-enter Army service (having retired on half-pay in 1815), he cites his place of residence for the last five years as Rumsey House, Calne. So I think that Samuel grew up there from the age of 9 and returned there once he left the Army in 1815, where his father was still living.

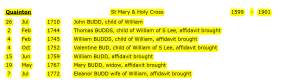

Interestingly, there are references to Budds living in Uxbridge from 1805 to 1812, with a William Budd cited as owning and living in property 1809 and 1810. I believe these references to be related to William Hayward Budd, William’s son (and not William snr), who married Mary Packer and had eight children over the period 1801-1813, all of whom were baptised at St Mary’s Church, Uxbridge.

Credit must go to Tim Wilkinson for his research into William’s death in Studley and sharing that with me.